On the go with the easel – The gardens of Monet

Before creating his famous garden in Giverny, where he eventually settled, Claude Monet had changed his place of residence quite a few times, and not only that, the master Impressionist habitually worked outside, bringing his easel and colours with him wherever he went. On the one hand, he was following the nature and specifically sought out certain places and areas for painting; on the other hand, he, a passionate lover of plants, built himself places of inspiration. Here, we present to you three of these places. Author Elisabeth Stursberg presents some of them here in sisterMAG.

- Text: Elisabeth Stursberg

On the go with the easel

The gardens of Monet

Before creating his famous garden in Giverny, where he eventually settled, Claude Monet had changed his place of residence quite a few times, and not only that, the master Impressionist habitually worked outside, bringing his easel and colours with him wherever he went. On the one hand, he was following the nature and specifically sought out certain places and areas for painting; on the other hand, he, a passionate lover of plants, built himself places of inspiration. Here, we present to you three of these places.

- Sainte-Adresse, Normandy

By the mid-1850s, Sainte-Adresse, a small town near Le Havre, had become a favourite summer destination of affluent locals. In one of the typical beach villas, the house of his aunt, the young Monet spent several summers. After the early death of his mother, his father’s sister became an important figure of reference for the aspiring painter who thus began developing his personal style in a distinctly familial environment. Much time was spent in the garden, which was varied and included a small forest and lawns as well as flowering hedges and beds. These early impressions without doubt influenced Monet’s view of nature as an artistic motif. However, he did not confine himself to the garden, but rather – enthusiastically – explored the surroundings, taking the easel with him wherever he went. His morning view of the port of Le Havre from 1872 which, instead of a classic motif description, he innovatively named Impression, Sunrise became the eponym of the entire movement and in retrospect is recognised as the »manifesto of a new genre« (arte, LINK 1).

- Argenteuil, Île-de-France

In December 1871, not long after the Franco-Prussian War had ended, Monet and his family moved into a house in Argenteuil. Formerly dominated by agriculture and vineyards, the town outside Paris was rapidly changing in the course of the progressing industrialisation, but nevertheless remained a popular destination especially for fans of water sports. Clearly inspired, Monet acquired a boat which he then converted into a studio. His colleague Eduard Manet, who liked spending time in Argenteuil just like him, captured »le bateau atelier« and Monet, depicting his wife, in a painting (Monet dans son bateau atelier, 1874). During the 1870s, Monet himself immortalised various motifs in Argenteuil such as the large bridge, the railway station and several boats anchoring in the harbour basin. Regarding the style, these works with their fragmented brushstrokes and spotted application of paint mark a highlight of Impressionism. Today, Argenteuil is still a popular destination for tourists wanting to follow in the footsteps of the Impressionists. The house on Boulevard Karl-Marx, where Monet lived with his family from 1871 to 1878, has since been renovated and is currently used by the Historical Society of Argenteuil. In the next years, however, it is supposed to be turned into a Monet Museum, helping visitors to experience the painters’ living conditions. In addition to an innovative presentation concept using virtual reality, the garden will thus also be replanted and restored to its original state, and even the floating studio is planned to be rebuilt.

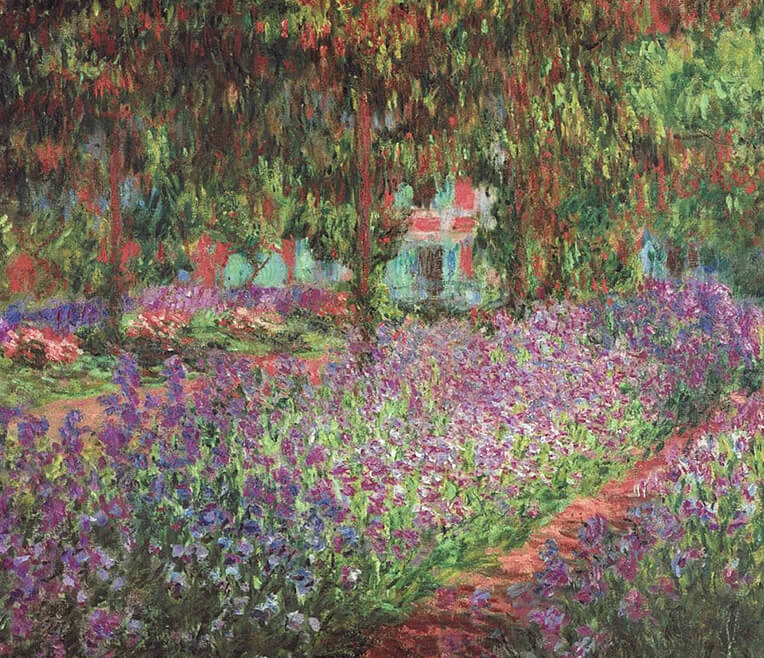

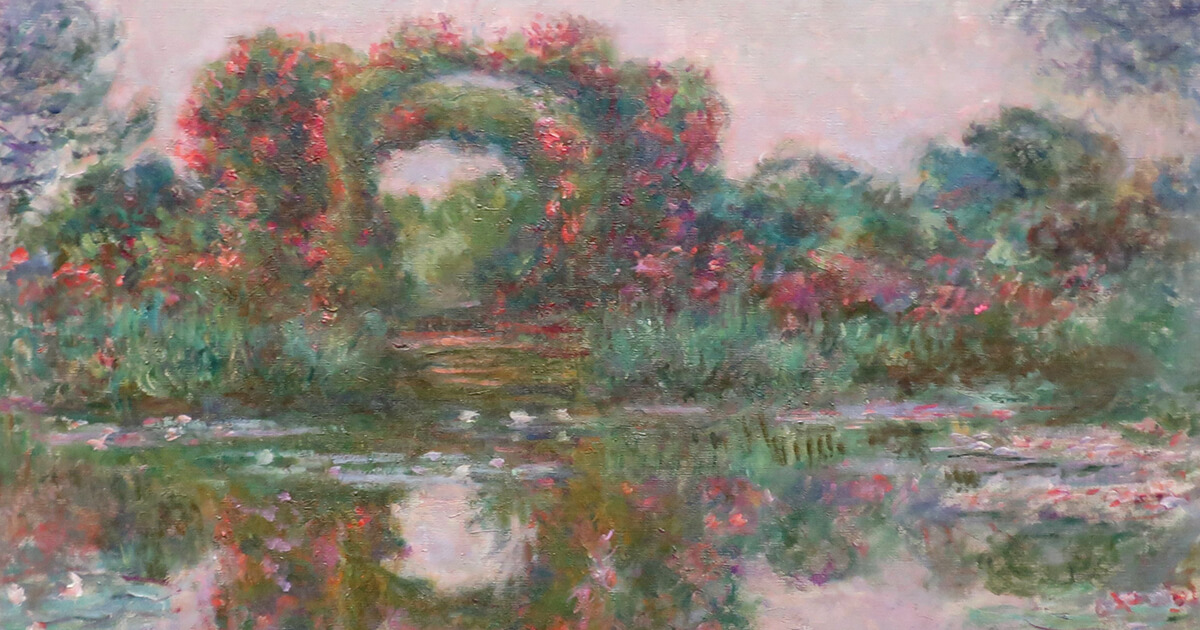

- Giverny, Normandy

Only a few years after Argenteuil, Monet, in 1883, found »his« place: a large house in Giverny, about 50 kilometres outside Paris, which he rented at first and where he moved in with his family. He would stay until his death in 1926. The basic features of one part of the soon famous garden, the flower garden closer to the house, were already laid out but there was nevertheless still a lot of work to be done. Given his precise ideas and the fact that Monet took his garden design rather seriously, it was also anything but an easy task. When the international popularity of his works rose, and soon after he was able to buy the house in 1890, Monet was in a financial position to also acquire the neighbouring property. Only then, ten years after moving in, could he finally begin to create the water garden he had been dreaming about. His gardens were never just a motif for him; they were close to his heart. Luckily, he could not rely only on the help of the whole family, he also frequently exchanged thoughts and ideas about gardens and plants, or plants for that matter, with friends such as Gustave Caillebotte, another plant lover. In general, he, who had always planted flowers in each of the many places he lived in, spent a good amount of money on his garden. He collected exotic plants, hired gardeners and built greenhouses to provide the right climate for exotic species. Stylistically, he designed the garden in the English tradition of using every free spot, giving each flower space and freedom to grow and ensuring that there was always something blooming. In Giverny, Monet created many of his most important works, for instance, the iconic water lilies. The house and garden today are a museum attracting more than half a million visitors each year. The garden is being maintained and kept as true to the original as possible, with only a few changes: The water garden, for example, can now be reached via an underpass since the road running between the two parts was simply less frequented in Monet’s day and could usually be crossed on foot.