Bauhaus Projects – Architecture & Aftermath

- Text: Michael Neubauer

Bauhaus Projects – Architecture & Aftermath

The Bauhaus Directors

- Walter Gropius Bauhaus Director, 1919 -1928, Weimar/Dessau

- Hannes Meyer Bauhaus Director, 1928 – 1930, Dessau

- Mies van der Rohe Bauhaus Director, 1930 – 1933, Dessau/Berlin

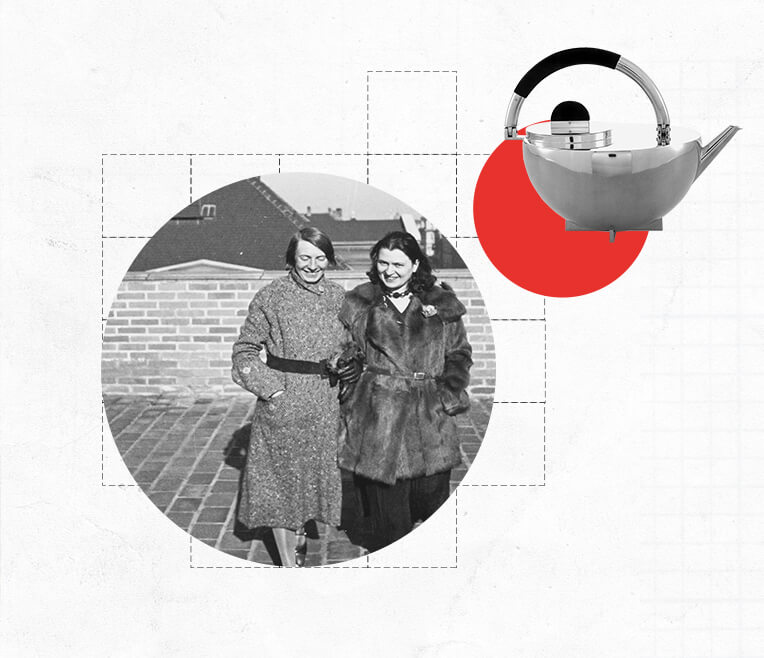

100 years of Bauhaus – a school not only of great importance for art and design, but above all for the architecture of the 20th century. It continues to influence these disciplines to this day. However, an architecture department wasn’t in the cards during the first years of Bauhaus. It was the school’s founder, Walter Gropius (1883 – 1969), who with his »Bauatelier«, which opened in Berlin in 1910, had a decisive influence on modern architecture throughout the school’s early history. His involvement contributed to the development of the school’s students and young masters. Standout projects include the Fagus factory building in Alfeld (1911-1925), the house of Dr. Fritz Otte in Berlin (1921-1922), and of course the Bauhaus building in Dessau (1925-1926). It was not until 1927 that Walter Gropius found his successor and independent head of the Bauhaus construction department: the Swiss architect Hannes Meyer (1889 – 1954).

Walter Gropius founded the »Staatliche Bauhaus« in Weimar on April 1, 1919, to use art and architecture to influence a new social beginning after the devastating First World War. His manifesto for its foundation points to this new approach:

»The Bauhaus strives for unity in all artistic creation; for the reunification of all artistic disciplines – sculpture, painting, arts, and handicrafts – to form a new architectural art of inseparable components.«

At the end of 1924, Walter Gropius and all the other Bauhaus masters reckoned with the consequences of the election of a right-wing Thuringian government. They left Weimar and found a new home in Dessau, where they built the Bauhaus for a second time. The school in Weimar was renamed the »Staatliche Bauhochschule Weimar« under the direction of architect Otto Bartnink (1883 – 1959).

It is little known that Otto Bartnink was also active in the Deutscher Werkbund (association of artists, architects, designers and industrialists) which also attracted Walter Gropius and other avant-gardists. He made a number of contributions to the discourse, such as: »Craftsmanship is the uniform means of any artistic activity. The natural development of craftsmen, architects, and visual artists is the evolution from craftsmanship to construction.«

So, who was the father of the Bauhaus philosophy?

Otto Bartnink surrounded himself with a number of former Bauhaus intellectuals with whom he began to challenge traditional ideas and struggle with emerging social changes – and ultimately lost. The Bauhochschule in Weimar was closed in 1930.

All these thoughts had a prelude and a conclusion. In the last decades of the 19th century, voices in art, philosophy, and the social sciences turned away from Wilhelmian narrowness to demand a freer, more authentic life that was closely connected with art. The result was an Art Nouveau style observed in architecture, fine arts and interior design, and arts schools, including life reform movements rooted in vegetarianism, naturopathy and nudism. Ideas for reform, which were to combine art with rapidly growing industrial advances, resulted in the »Deutscher Werkbund«, founded in 1907. »Good form« was an expression of quality and objectivity. Emphasis on content and form favoured functional thinking in goods production, furniture construction and architecture. Peter Behrens (1868 – 1940), an industrial designer, was a pioneer, founding member, and among the most excellent representatives of this new school of thought. Among others, he was the designer of the Berlin AEG turbine hall, in whose office Walter Gropius worked. For Behrens, this was a unique opportunity to follow discussions and developments on architecture in Germany and beyond. His strong personality, respected writings, contacts and great organisational talent inspired Gropius to found the Bauhaus.

Everything had its aftermath. Walter Gropius initially demanded the unity of trades during the »romantic« Bauhaus phase, especially the importance of craftsmanship in the sense of earlier »Bauhütten«. However, rapid industrial progress forced him to reconsider as early as 1923. He reformulated the model of the Bauhaus apprenticeship into »Art and Technology – the New Unity«. The second director of the Bauhaus, Hannes Meyer, who emphasized architecture even more, oriented his work towards aggravating social conditions. Among other things, he created the Bundesschule des Allgemeinen Deutschen Gewerkschaftsbundes (ADGB Trade Union School) together with the architect Hans Wittwer. The global economic crisis of 1929 and 1930 brought forth political questions. Meyer’s slogan, »The needs of the people instead of the need for luxury«, and his handling of communist tendencies among students, finally led to his dismissal.

When the Nazi regime began, the third director of the Bauhaus, Mies van der Rohe (1886 – 1969), who had meanwhile moved to Berlin, was forced to close the school in 1933. »Art Bolshevism«, as the Bauhaus was called, was declared to have no future in Germany. While Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich’s German Pavilion at the 1929 International World Exhibition in Barcelona – with a house airily gliding along in nature – attracted great attention, van der Rohe could only realize his vision in the distant future. For example, in shaping the cityscape of Chicago.

The actual aftermath had begun; Bauhaus as a philosophy had not died. Throughout the world, buildings by architects or students of the Bauhaus bear witness to this. They can be found in Chile, in the USA, in Wroclaw, Brno, Königsberg, and especially in Tel Aviv (the »White City«).

Furthermore, the modern ideas of the Bauhaus were spread by other institutions:

- New Bauhaus and School of Design, in Chicago

- Black Mountain College, in North Carolina

- Hochschule für Gestaltung, in Ulm

New Bauhaus and School of Design, Chicago

From 1937 to 1949

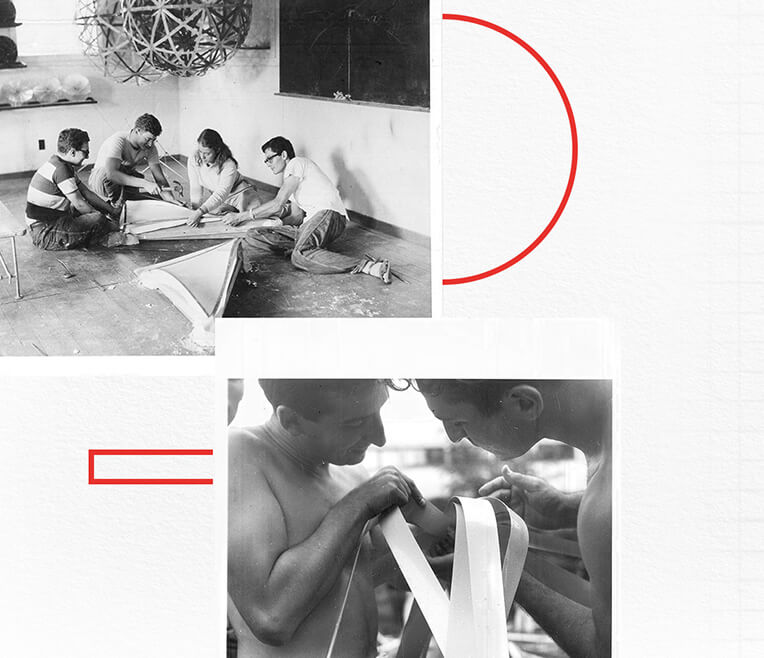

The economy also provided impetus for Bauhaus’s foundation in America in the form of the »Chicago Association of Arts and Industries«. American interest in the German Bauhaus culminated in 1938 in the exhibition »Bauhaus 1919 to 1928« at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. On Walter Gropius’s recommendation, former Bauhaus colleague László Moholy-Nagy (1895 – 1946) was appointed director. Other former Bauhausers also found employment across the pond. The teaching program followed the models of Weimar and Dessau very closely, naturally incorporating new scientific findings. All art movements, supplemented by photography in interplay with technology and science, were included in the curriculum. The school became a veritable elite forge of modern American design. However, soon skepticism

arose among donors when they did not accept Moholy-Nagy’s modern teaching methods as purposeful. Financial support failed to materialize, and new companies were founded with other donors under the name »School of Design« in 1939 and again in 1944 as the »Institute of Design«. László Moholy-Nagy’s premature death was a big setback and the school was ultimately bailed out in 1949 through its incorporation into the »Illinois Institute of Technology«, led by Mies van der Rohe.

Black Mountain College, North Carolinas

From 1933 to 1956

In addition to Josef Albers (»Homage to the Square«, 1949), an established Bauhaus master, famous teachers such as John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Willem de Kooning, Lyonel Feininger, Walter Gropius, Charles Olsen, Alexander Schawinsky, Cy Twombly and Robert Rauschenberg taught at this college. The director was the founder John Andrew Rice, an advocate of modern teaching methods such as »learning by doing«. It was a very liberal school without a fixed curriculum, including subjects of fine arts and humanistic teaching. Regular discussions about all matters of education and social problems took place between students and teachers. The entire school body was involved in the administration and maintenance of the institute, and the Bauhaus philosophy was guaranteed by Josef Albers. The curriculum followed his guidelines and teaching. Summer and art courses complemented the program. Money problems were also a limiting factor at this college. This was exacerbated by the campus’s isolated location in a very conservative society, which defended itself against left-liberal approaches. Several attempts to save the school by structural changes failed, leading to the dissolution of Black Mountain College in 1956.

Hochschule für Gestaltung, Ulm

From 1953 to 1968

After the Second World War, attempts were made in Germany as well to take up Bauhaus ideas and pass them on in teaching. Inspired by Inge Scholl, sister of Hans and Sophie Scholl, an art academy was founded in Ulm to answer artistic and political questions about the consequences of the Nazi regime in a democratic way. Leading teachers came together for this task: Max Bill as director; Tomas Maldonado; Max Bense and Alexander Kluge. However, art, architecture and design remained marginal aspects of education. Unfortunately, the ideas of the protagonists were divided between more artistic design of everyday objects (Max Bill) and an industrial design geared to mass production (Tomas Maldonado). Max Bill eventually resigned as director. As the relationship to the original Bauhaus concepts increasingly faded, with education based more and more on technology and science, »art« students became displeased with the curriculum. Not least as a result of the ’68 student movement, the university was closed during the same year.

1923 Oskar Schlemmer:

A »struggle of the spirits like perhaps nowhere else, a constant restlessness that forces the individual almost daily to take a fundamental stand on deep-seated problems. Depending on the individual’s temperament, he suffers from this diversity, finds it his greatest pleasure, is fragmented by it, or it strengthens him in his conviction.«

2019 Richard Siegal:

»All contemporary art ultimately stands on the shoulders of the Bauhaus as that is where ideas which still form the foundation for many artists today, were first brought together.«