Lichtenstein & Mad Men – The Drapers take a Drive

I was unfamiliar with Roy Lichtenstein’s »In the Car« before it was introduced as the centrepiece of the current sisterMAG issue. But I knew the subjects all the same: the couple in motion were Don and Betty Draper, the protagonists of the hit show Mad Men. This is chronologically impossible, of course, as Lichtenstein’s painting debuted more than four decades before the first episode of Mad Men aired. (The source scene of »In the Car« was illustrated by Tony Abruzzo in the September 1961 issue of the Girls’ Romances comic anthology; Lichtenstein’s pop art adaptation came in 1963). Still, in studying the Drapers’s melancholic relationship we can glean from Lichtenstein’s work the moods and mores of marriage in the ’60s.

- Text: Christian Näthler

- Illustrations: Daniel Graf

Lichtenstein & Mad Men – The Drapers take a Drive

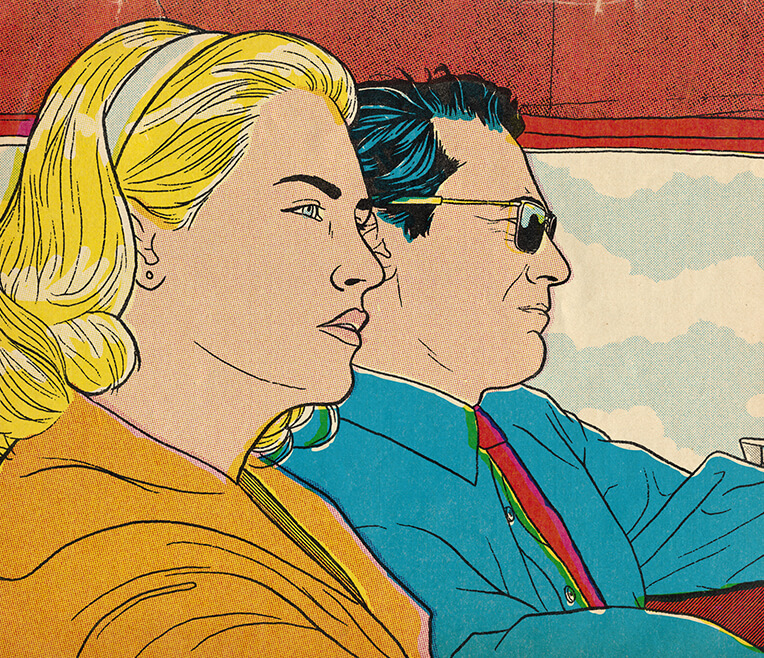

What the subjects of Roy Lichtenstein’s »In the Car« tell us about domestic partnerships in the 1960s in consideration of Mad Men’s Don and Betty Draper.

I was unfamiliar with Roy Lichtenstein’s »In the Car« before it was introduced as the centrepiece of the current sisterMAG issue. But I knew the subjects all the same: the couple in motion were Don and Betty Draper, the protagonists of HBO’s hit show Mad Men. This is chronologically impossible, of course, as Lichtenstein’s painting debuted more than four decades before the first episode of Mad Men aired. (The source scene of »In the Car« was illustrated by Tony Abruzzo in the September 1961 issue of the Girls’ Romances comic anthology; Lichtenstein’s pop art adaptation came in 1963). Still, in studying the Drapers’s melancholic relationship we can glean from Lichtenstein’s work the moods and mores of marriage in the ’60s.

A bobbed blonde draped in luxury. A slick sir in a power suit casting an imperial glance over his domain. A Master of the Universe and his trophy wife. Looking at Roy Lichtenstein’s 1963 pop art painting »In the Car«, it’s easy to imagine the couple as Don and Betty Draper of Mad Men, HBO’s hit television series. The superficial likeness is evident, but there’s also much more at play.

Mad Men is set in New York City in the 1960s, a period in which the ways of doing things made way for ways in which they could be done. But while winds of change swept through the streets and speakeasies and the advertising agencies of Sixth Avenue, the air in the suburban household remained stagnant. In the early ’60s, men spent increasingly more time out of the house, unmarried women started to open doors, and for wives at home the walls were closing in. Many of these women were defined only in relation to the men in their lives and suffered from a profound lack of identity as their husbands hit the town – and Pan Am runways – looking for fun. In their confinement they also they saw how women not duty-bound to domestic responsibilities were finding their own footing outside the home. As any Instagram addict will tell you, adriftness and envy are a dangerous mix. Married women became devastatingly bored with their domestic lives, and husbands became irredeemably unsatisfied with their domestic wives. It is no wonder adultery tears through every marriage in Mad Men, which remarkably captures the social, cultural and political flux of American life in the postwar era.

This is the story I see when I observe the couple in the car. The gentleman smirks with all the leverage in the world over a woman not naive but nevertheless powerless. Love is so far gone that sadness and rage no longer register for her. There are no other avenues to explore. What else can she do in light of her husband’s unrepentant infidelity but be a passenger in the charade? Well, there is one thing: find the next economic stepping stone. (In Mad Men, Betty has an affair with Henry Francis, a high-ranking government official whom she marries after divorcing Don). It’s a pretty depressing situation, really: rove from one patron to the next in everlasting pursuit of the Joneses or smile your way through misery. The woman in the car languishes in the ennui of being stuck in between.

A similar powerlessness plagues Trudy Campbell, whose cheating husband, Peter, works with Don. Alison Brie, the actress who plays Trudy, speaks about her character’s struggle: »Like most women at that time, Trudy is able to turn a blind eye to anything she finds off-putting for as long as she is able«, she said in a 2013 interview with The Guardian. »Trudy had always been concerned with what others think, so she’s able to project a state of sunniness in public, even if things at home aren’t perfect.«[1]

Other notable Lichtenstein works from the period hint at the plight of a ’60s housewife. In »M-Maybe«, from 1965, we see an uneasy woman ponder the whereabouts of her man. »M–Maybe he became ill and couldn’t leave the studio«, she posits. »Ohhh…Alright…«, from 1964, is more vague – until we take a closer at the source from which it was adapted. In the original work, the 88th issue of the comic Secret Hearts, we see that the woman is replying to who is presumably her husband on the other end of the telephone. »I’m sorry, Nancy, but I’ll have to break up our date! I have an important business appointment. I’ll see you tomorrow night!« he says.[2] It’s not difficult to read between the lines.

Back to the title piece. We do not know anything about the man and woman in the fancy red car, but we can look at Don and Betty Draper’s relationship in Mad Men – a representation of many domestic partnerships in the early 1960s – to draw conclusions about the scene.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2013/apr/05/what-mad-men-says-about-women

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ohhh…Alright…#/media/File:Ohhh…Alright…_source.jpg