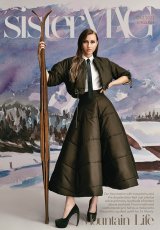

Payne’s Grey – When a Colour is a Feeling

Prussian blue, yellow ochre and crimson lake: who would have thought these vivacious hues combine to feel like a completely joyless winter day. Such is the mood of Payne’s grey, a colour you can’t unfeel once you’ve seen it. Learn more about it from the author Christian Näthler in sisterMAG.

- Text: Christian Näthler

When a Colour is a Feeling

Ask me to paint a picture of melancholy, and I’ll dip my brush in Payne’s grey.

Prussian blue, yellow ochre and crimson lake: who would have thought these vivacious hues combine to feel like a completely joyless winter day. Such is the mood of Payne’s grey, a colour you can’t unfeel once you’ve seen it.

Most painters probably owe more to Payne than Van Gogh or Monet.

Yes, the William Payne. The watercolourist? Ah, you must not have read the 1912 book Color Standards and Color Nomenclature. Ok, I’ll slow down.

Born in Exeter in 1760, Payne worked as a civil engineer before finding vocation in painting. The rather-be artist eventually settled in London, though he remained rural, painting scenes from what the rest of London called the sticks. It wasn’t so much the topography that spoke to him, but rather the mood. When he began teaching as an art lecturer, he urged his students not to paint what they saw, but to paint what they felt (my words, not his). Payne was a poet among draughtsmen, more Wordsworth than Hemingway.

Masterful teacher that he was, Payne himself struggled to produce anything of praise. While many of his contemporaries stroked the fashions of Britain’s esteemed watercolour societies, his work stagnated, and even regressed. Payne’s mention in the Dictionary of National Biography, the who’s who of notable British figures, notes that by 1812 his art had »degenerated into mannerism«. Ouch. Imagine entering the Regency with a Baroque accent. How passé. Alas, »he was surpassed by better artists and forgotten« before his death in 1830.

Like many artists, Payne wasn’t famous until he died. His claim is a happy little accident (R.I.P. Bob Ross) called Payne’s grey, a bluish-grey colour that left painters questioning the existence of black. It came to life when he ballparked a mix of Prussian blue, yellow ochre and crimson lake. Pleasant hues on their own, together they look like wet cigar ash drying in the sun. Payne’s grey is the perfect colour for painting something that exists over yonder. Picture the New York City skyline on the horizon. Munich’s alpine backdrop. Before Payne’s grey, it was common to paint dusky objects in the middle and extreme distance in watered-down shades of black.

At its lightest, Payne’s grey is Monet’s winter shadows. At its darkest, it is the Titanic sinking into the obsidian sea under a starry sky. Somewhere in the middle are Parisian rooftops on a stormy day. For me, it is winter in Berlin. Colour author Katy Kelleher, writing for The Awl, calls it a »long aching darkness«, »moody and damp«, »foreboding and quiet«[1]. Tell me that doesn’t sound like a tram stop in Hohenschönhausen on a completely joyless January day. When Robert Lewandowski misses a match-winning 94th-minute sitter at the Alten Försterei in mid-March, he’ll drop to his knees and look to the Payne’s grey heavens above Köpenick.

How can a colour evoke so many vibes? As Kelleher explains, Payne mixing colours was like »a chef cooking to taste … he didn’t have a set recipe«. In 2003, an investigative painter looked up which hues nine leading watercolour manufacturers used to concoct their branded Payne’s greys. Each had a different formula. »I just can’t wrap my head around the variety of pigments. There is no standardization and some of the colours don’t make sense«, she wrote. Holbein uses four: Alizarin Crimson, Antwerp Blue, Ultramarine Blue and Lamp Black. Da Vinci just two: Lamp Black and Prussian Blue. Some go as far as Quinacridone Violet.

The next time you see Payne’s grey in a painting, don’t be surprised if it creeps from the canvas to touch you, its damp air feels cool on the tip of your nose and settles into your bones. Because there will be a next time: like a word you’ve just learned, you’ll start to see it everywhere. And probably feel it too. Alas, seasonal depression is just around the corner. Ask me to paint a picture of this melancholy and I’ll dip my brush in Payne’s grey.

[1] https://www.theawl.com/2018/01/paynes-gray-the-color-of-english-rain-and-henry-millers-paris/