Women at the Bauhaus – »Woven Modernism«

A theme that is gladly taken up and illuminated in the anniversary year of the Bauhaus: the women at the Bauhaus who stood for a long time in the shadow of the school. In sisterMAG, our authors introduce some important »Bauhaus women«: Marianne Brandt, Gunta Stölzl, Ise Frank, Dörte Helm and Alma Mahler-Werfel (also: Alma Gropius).

- Text: Victoria Beier, Lisa Striegler, Sophia Schmidts , Bianca Demsa

Women at Bauhaus

»Woven Modernism«

The Bauhaus movement is often regarded as THE quintessence of the early 20th-century avant-garde in Germany. Many art lovers find themselves caught up in the flair of its time and the aura of the renowned artists at the world-famous school.

But the image of this exemplary democratic institution might not always be as it seems. For a long time, women in particular, were left in the schools’ shadow, although their work and vision had a fundamental influence on Bauhaus art. When Walter Gropius opened his Bauhaus school in Weimar in 1919, he announced in his programme: »Every person without exception is accepted as an apprentice, regardless of age and gender; and whose talent and previous training is considered sufficient by the Master’s Council.« In fact, there were more female than male applicants in that first semester.

After the war, women gained new self-confidence. They came to Bauhaus in the hope and expectation of being able to explore new possibilities. The democratic constitution of the Weimar Republic granted them the right to study and vote for the first time.

In practice however, things were different. Gropius demanded strict separation of the students. Johannes Itten claimed that women had »a weakness« in three-dimensional vision. Oskar Schlemmer coined the sentence: »Where there is wool, there is also a woman who weaves, even if only to pass the time.« Inevitably, this meant entering the weaving mill and working on two-dimensional objects. Unfortunately, this tension between the women’s professional desires, their love of experimentation and the traditional gender thinking at the Weimar Bauhaus remained so for the long term.

From 1920 onwards, the weaving mill was designated as »women’s work«. This attempt to reduce the female students to their roles as weavers culminated in an enormous surge in industrial design development and a re-evaluation of textile art. Step by step women succeeded in penetrating the classical male domains and creating outstanding artistic achievements. Among the most successful Bauhaus women were the metal artist Marianne Brandt, the painter Lou Scheper, the photographer Lucia Moholy and the designer Lilly Reich. At the Bauhaus Dessau, the fusion of art and technology was strongly encouraged. Women took up this combination enthusiastically. Anni Albers, a weaving student, unlocked her innovative potential by developing industrial materials. Others successfully had their inventions contracted or were granted patents for their ideas.

The work and vision of these women has had a lasting and significant impact on Bauhaus art. The history of the Bauhaus is no longer just a history of male artists. It is time to shine a spotlight on these talented women and their incredible achievements. And raise them up to the same level as a Kandinsky, Schlemmer or Itten.

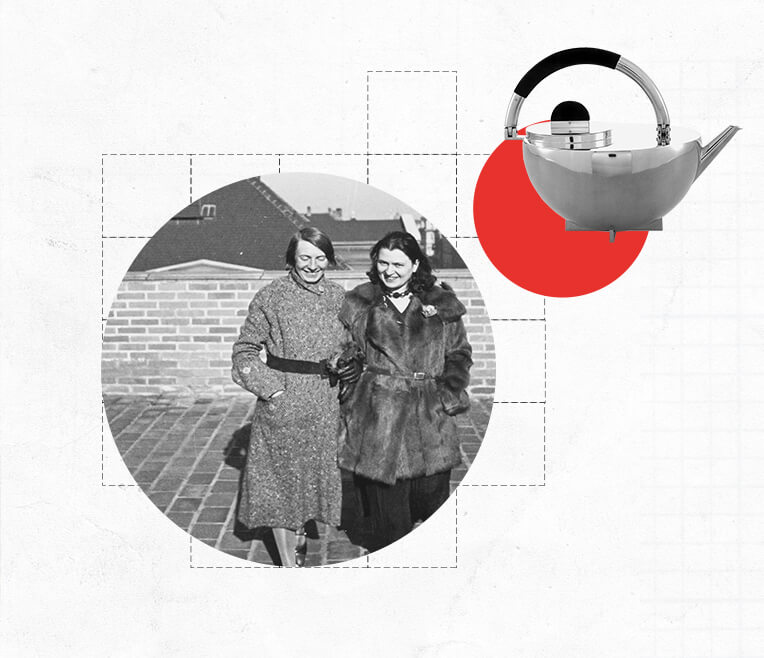

Women at Bauhaus: Marianne Brandt (1893-1983)

MT 49 – four letters which are unmistakably Marianne Brandt

They refer to her silver and ebony teapot, which holds the record for the highest price ever paid for a Bauhaus object – in 2007: 361,000 US dollars. Created by a visionary metal designer whose spherical and flat jugs, sugar bowls and ashtrays are among the most famous Bauhaus designs ever made.

»It wasn’t a warm welcome at first. The general opinion: A woman doesn’t belong in the metal workshop. This meant assigning me mainly boring, tedious tasks.«

Nevertheless, the metal artist succeeded in gaining a foothold in the Bauhaus workshop. Marianne Brandt grew up in a middle-class family in Chemnitz. Her father was a lawyer and an advocator of the theatre and fine arts. At 18, she studied painting at the Grand Ducal-Saxon Academy of Fine Arts in Weimar. In the summer of 1923, a large Bauhaus exhibition held in Weimar opened her eyes. She gave up painting, seeing no money in it, and switched to the Bauhaus school.

The five years in Weimar and Dessau became her most prosperous as a metal designer, and the Hungarian, Moholy-Nagy, was her most important mentor.

It wasn’t long before she had set new standards for the metal design of the classical modern age. In 1928 she was appointed deputy master. Brandt was also considered an innovative artist in the photography field. In 1933, her career, like that of many other Bauhaus women, was cut dramatically short. Even later on, there was no room for her experimental design in the GDR. As a metal designer, industrial designer and photographer, Marianne Brandt is an important part of our 20th-century art history. Her tea extract jug is still regarded as an icon of Bauhaus design today, and her designs always attached great importance to functionality:

»…No jug has ever left our workshop, which was not drip-free.«.

Women at Bauhaus: Gunta Stölzl (1897-1983)

Gunta Stölzl was one of the most successful Bauhaus women and paved the way for modern textile design. Despite her talent and assertiveness, she didn’t always have it easy. Unlike Marianne Brandt for example, she wasn’t sponsored by a Bauhaus master. In 1927 she became the first female teacher to take over the entire management of the Bauhaus weaving mill at Dessau.

Adelgunde Stölzl was born in Munich. After seven semesters at the somewhat conservative Munich School of Applied Arts, she joined the Weimar Bauhaus in 1919 at the age of 22. So impressed was she by the reform ideas of Walter Gropius that she enrolled a second time. In October 1919 she wrote in her diary:

»…nothing is inhibiting about my outer life, I can shape it as I like. So often have I dreamt about this and now it has finally come true (…).«

Gunta Stölzl combined the principles of modern design with sound craftsmanship. The influence of Johannes Itten’s contrast theory is particularly evident in the colour choice for her Bauhaus designs. Her weaving mill fitted out the theatre café in Dessau, she developed upholstery fabrics for Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel chairs and exhibited at the Leipzig trade fairs. Towards the end of the 1920s, she married the left-wing Jewish architect Arieh Sharon, but political change was on the horizon. In 1931, she was forced to resign her position and move with her family to Switzerland, where she ran her own weaving mill in Zurich. Her carpets lived life’s rhythm, breathed richness of form and did not follow a trend. »It was necessary to clarify our imagination, shape our experiences through material, rhythm, proportion, colour and form«. The excessive colourfulness of her early work in particular, radiates an atmosphere reminiscent of jazz and expressive dance. Her work still connects us to a colourful Bauhaus life, how it might have been.

Women at Bauhaus: Ise Frank (1897-1983)

GREAT, SAD MOMENTS

If you leaf through the countless piles of Bauhaus books, you won’t find her name on any of the front pages. She doesn’t adorn the title of any documentary nor does there seem to be any real information about the second wife of the world-famous Walter Gropius. Yet, Ise Frank deserves nothing less than a glamorous VIP seat in the very front row.

»Behind every successful man is a strong woman.« A supposedly simple truth, but also a clever generalisation stating the obvious: There is no hiding behind that broad successful back, no support at all costs. His needs must be recognised and met, his ideas saved. A burden which feels like the heavens collapsing and the endless struggle continues to find your own identity.

BEING NEEDED AND THINKING AHEAD

A few semesters of German studies and work in a bookshop led Ise Frank to a yet undiscovered passion: writing. As an editor and secretary, she loved nothing more than a challenging word game. In 1923, at the age of 26, she married Walter Gropius and his Bauhaus idea in Weimar. An idea which she continued to pursue and struggle with at the same time. She formulated his letters, lectures and articles until she finally gained the necessary freedom to work on her own writing career. In a whirlwind of uncertainty, she lost their unborn child as well as Gropius on occasion.

AN ESCAPE FROM THE PAIN

Ise Frank was vulnerable.

She would see herself as uprooted and lost. Feelings of being expected or coming home were alien to her. One summer in Paris she was taken in by her trusted friend Irene Hecht »during a week-long free fall« as Jana Revedin so heartrendingly describes, in her biography »Everyone here calls me Frau Bauhaus«. Irene gave Ise the closeness and stability she was so deprived of in her relationship with Walter Gropius. Warm croissants and cafe latte became their staple of a comforting home; a place which became »their place«.

Women at Bauhaus: Dörte Helm (1887-1941)

If you search for a picture of Dörte Helm, you will find a sea of actresses faces, but not Dörte Helm herself.

The artist from Rostock was a versatile talent. She worked as a graphic artist, painted city skylines and landscapes and played a major role in the interior design of the »Haus Sommerfeld« at the Weimar Bauhaus. Nevertheless, she was demoted not just once, but twice to lover status by German television during the Bauhaus 100th anniversary. First as an adulteress to a fictitious couple and then as the affair of Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius. A fact that was never proven. Dörte Helm was born in Berlin in 1898, daughter to a philologist father and a Jewish mother. Her artistic talent was apparent early on. Helm gave art lessons and spent three years studying sculpture and drawing in Kassel after graduating from a girls’ school in Rostock. This led to her move to Weimar in 1918. Although it was a common fear at the Bauhaus, that the men would lose their valuable workshop positions to the women, Helm earned herself a space in the dominantly male domain of mural painting. In 1922 she passed the apprenticeship exams in decorative painting.

One year later, 20 postcards were created for the large Bauhaus exhibition and only one was designed by a woman: Dörte Helm.

Back in Rostock, the young unconventional thinker had a hard time establishing herself. Her strict father didn’t think much of the avant-garde Bauhaus ideas and living together with him was like suffering in silence. She married the journalist Heinrich Heise and they moved to Hamburg together where she worked as a writer. As a »half-jew« she was forbidden to work by the Nazis in 1933, yet continued writing under a pseudonym. She died at the young age of 42 of an infectious disease. To this day, Dörte Helm is an example of the ever-present gap and lack of reflection concerning women in the arts and proof that television is still not prepared to tell the story of a strong woman without putting a famous man at her side.

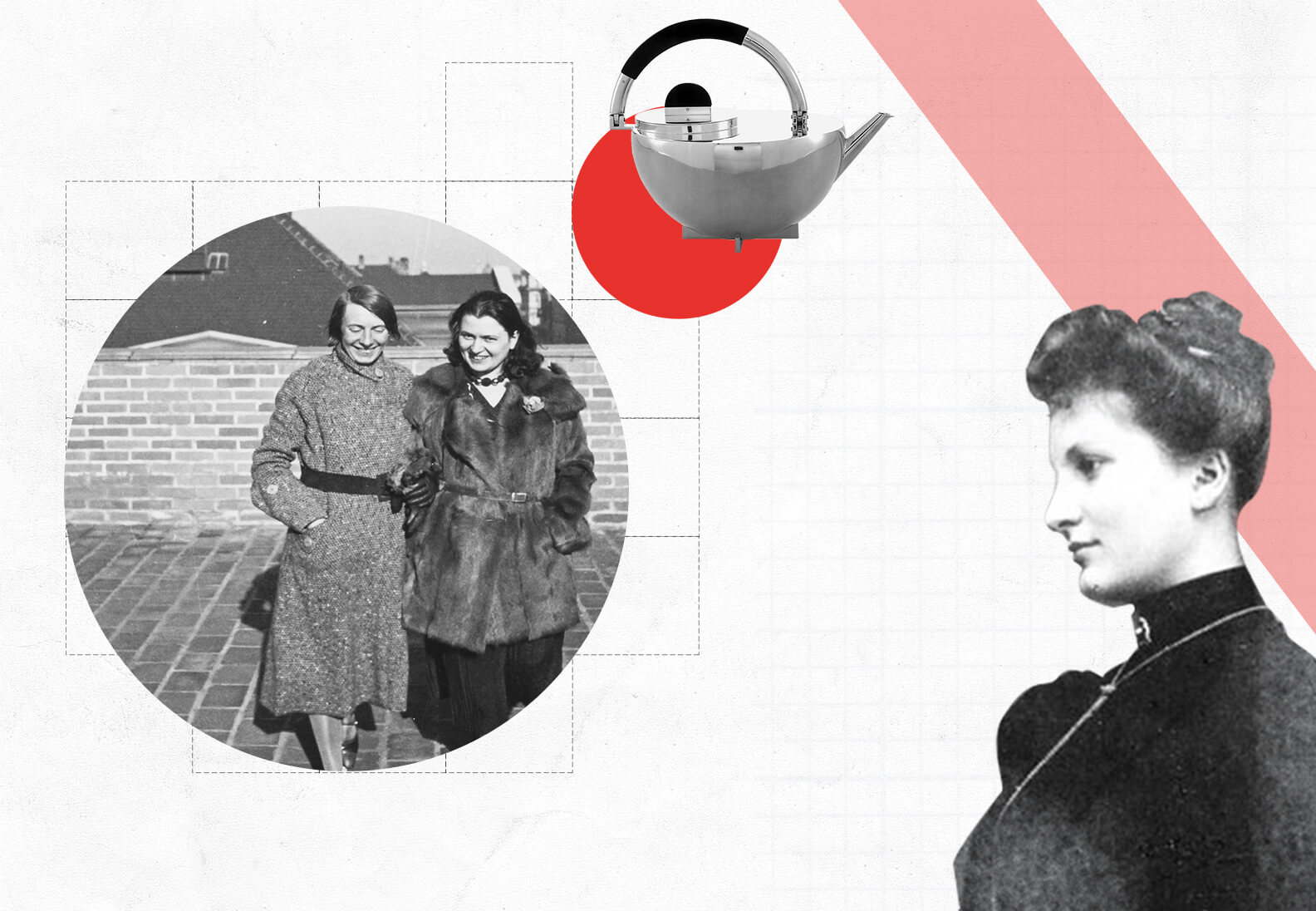

Women at Bauhaus: Alma Mahler-Werfel (1879-1964)

A muse, femme fatale and a secret composer.

Alma Gropius was a complex personality with an extraordinary and multifaceted life. Not just the wife of Walther Gropius, she was a socialite, writer, and composer of over 100 songs.

Born in 1879, Alma’s father Emil Jakob was a renowned Viennese landscape painter, her mother a singer and step-father Carl Moll.

Her beauty, intelligence and charm drew countless influential suitors in. One of her first loves, the 18 year older Gustav Klimt. Alma soireed with the likes of Thomas Mann, Richard Strauss and many more famous artisans of the salon scenes in Vienna, Los Angeles and New York and was known as an intellectual muse.

It was during her difficult marriage to Gustav Mahler and the loss of her daughter Maria that she met Walther Gropius during a stay at the Wildbad Clinic in Austria. After a five year on-off affair and now a rich widow, she travelled to Berlin in 1915 to profess her undying love for Gropius.

Their marriage was also not an easy one. Alma’s need for social standing created disharmony. The experience of the war shaped Gropius’s ambition and led him to the Bauhaus movement. A vision which Alma didn’t share. Daughter Manon was born but things came to a head when Gropius discovered her affair with Franz Werfel and an illegitimate son. He granted Alma a quickie divorce in 1920 by claiming fault and let himself be caught in flagranti with a prostitute.

Alma fled to Los Angeles with Werfel, continued her salon and wrote her criticised 1960 autobiography which portrayed various unflattering portraits including Gropius. She died aged 84 in New York in 1964 and was laid to rest in Vienna in 1965.

Misunderstood or not, Alma had immeasurable creativity. She studied composition with Josef Labor, Alexander von Zemlinsky and Max Burckhard. She composed instrumental pieces, an opera and over 100 songs. Musical talent that was then stifled. Only 17 exist today but create an everlasting legacy.