Monumental Friendships: Rodin and Rilke

The friendship between Rodin and Rilke is the prime example of an ambivalent relationship between two great artists that went through the stages of early emotional connection, close collaboration and the inevitable estrangement. For this sisterMAG issue, Robert Eberhardt gave us insight into the work and souls of two artistic heavyweights of the 20th century.

- Text: Robert Eberhardt

The monumental friendship between Rodin and Rilke

The friendship between Rodin and Rilke is the prime example of an ambivalent relationship between two great artists that went through the stages of early emotional connection, close collaboration and the inevitable estrangement. The artistic results of their collaboration show much more than a personal connection and give insight into the work and lives of two heroes of art of the 20th century.

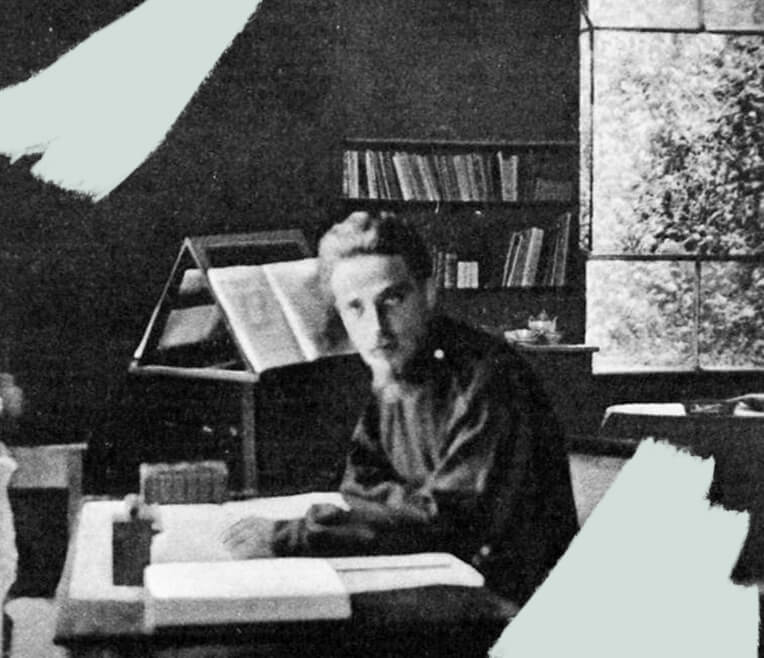

At 25 years old, poet and writer Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) met the then 61 year old and world-renowned Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) on September 1st, 1902 in Paris. Back then, Rilke was writing a book about the French sculptor that he would finish towards the end of 1902. In 1905, Rilke returned to Paris, moving to Rodin’s estate in Meudon, located just outside the city, and became his secretary. He corresponded with admirers from Germany, kept in touch with publishers and magazines, became an expert on all aspects of Rodin’s work and life, travelled to give talks about the artist and spread his fame.

As Austrian writer Stefan Zweig (1881-1932) would later write about the meeting of those two artists and the ambitions of the young poet who sought to impress with airy words instead of hard rock: »The fickle thing we would call coincidence brought Rilke to Paris, where he became Rodin’s secretary and lived in those lofty, hallowed halls out in Meudon, where there were white and pristine works, a wood made from stone that was still separated in its parts by the emptiness of space and the inner finality of its outlines. He saw the old master with his dividing power and he was tempted to be like him, to make his written material as final and strict as Rodin plastically formed his portraits of the world – to shape glass-like verses into the same harsh lines as Rodin did with the marbled weight of earth-grown stone.«

For Rilke, his time with Rodin was an education in seeing – he closely followed the origination of every piece as well as their distribution and Rodin’s integration into the high society of Paris and its art market. In hindsight, their collaboration appears to be a classic master-student that mostly shaped the younger student’s creative development.

But only one year later, in 1906, the close collaboration came to a sudden end – and Rodin and Rilke did not part as friends. They met time and time again and for a while, Rilke even lived at the Hotel Biron (Rodin’s Parisian Townhouse from 1908 and the present-day Musée Rodin), but they never grew truly close again.

In 2001, the letters written between the two artists were published in German. Mostly from Rilke’s pen, since Rodin used written communication mostly for exchanging necessary information, the letters show a deep and soulful view on art theory and other matters. They express the current state and worldview of the young poet that originally idolised the old master. Rilke captured many reflections and quotes by Maître Rodin: »You can do nothing but work. Work and be patient.« or »The artist has to return to God’s original text.«

In his first letters to Rodin in the summer of 1902 , Rilke writes: »I want to thank you again for your great letter and want to greet you, my noble master, with all my admiration.« As the letters progress, a certain disenchantment and emotional conflict appears between the lines. The ideal picture of the sculptor who made those appealing, sensual, anthropomorphic works could not stand up to reality. Rilke’s view of an artist as a genius and disconnected viewer of the world, as a human combination of spirit and matter did not conform to everyday life. Rodin might have been a great artist, but he was also a regular human being. When he was done working, he behaved like any Parisian man; went out, had (short-lived) relationships with several mistresses and was bored. Slowly, the myth of Rodin faded in the eyes of the young poet. It appeared like Rodin was no floating cosmic flâneur but merely a great craftsman. While it was agreed that Rilke would work for Rodin two hours a day, this allotted time was far from enough for the overburdened poet, who’s French was not good enough to quickly deal with correspondence. After a row about a simple misunderstanding, Rodin harshly fired Rilke with immediate effects. Because he disagreed, Rilke at first kept up giving talks about Rodin.

Many other things separated the two greats: While Rodin was bound to his beloved Paris, Rilke was a free spirit; never in one place for too long. He stayed with friends and in luxury hotels as he made his way through Europe and its contemplative and exquisite towns and wandering became the core of his art. He spent the last five years of his life in an isolated stone tower in the Swiss canton of Wallis, where he died from leukaemia in 1926.

The relationship between Rodin and Rilke is a prime example for the temporary collaboration between two artists: an intense balance of closeness and distance, of gleaming admiration and bitter disappointment and the shaping of all of these things into incomparable art – in this case, the grandest poems of the century and iconic sculptures that are still known around the world and sold at high prices.

Those who would like to learn more about the special relationship between the two artists should definitely read the recommended book (with much additional information) that deeply elaborates on said friendship. If possible, take the book to the beautiful gardens of the Musée Rodin in Paris – a view of fresh, green chestnut trees and the pretty limestone façade of this hôtel particulier (Rodin lived there between 1908 and 1917) will make reading even more worthwhile. After his death in 1917, Rodin was buried underneath »The Thinker« on the grounds of the estate that he bought in 1895 to have a quiet place in addition to his studio in Paris.