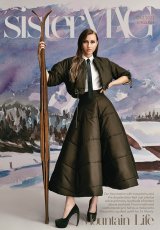

The enduring democracy of the blouse

The biography of the blouse is a story of swings settling in equilibrium – from peasantry to posh to class agnostic, and from male to female to androgynous. The whole story of the blouse here in sisterMAG by author Christian Nathler.

- Text: Christian Nathler

The enduring democracy of the blouse

Tracing the history of a garment for the people

The biography of the blouse is a story of swings settling in equilibrium – from peasantry to posh to class agnostic, and from male to female to androgynous.

Though the blouse has been a mostly unfamiliar entity in my life, I do have notions of the things I do not know. My personal history with it dates back about 20 years; I remember my mom trying not to burn hers with an iron. To my understanding, it is a women’s garment. But the one I remember most is the “puffy shirt” worn by Jerry Seinfeld while promoting a benefit to clothe the homeless. Elaine, who set up the benefit, is incensed by Jerry’s pageantry: “You’re supposed to be a compassionate person! That cares about poor people! You look like you’re gonna swing in on a chandelier!” She likens him to the Count of Monte Cristo, of the eponymous 1844 novel by Alexander Dumas. A more recent, sartorially fitting comparison might be the pirate Jack Sparrow.

Fact is, the blouse has a more humble history. The term is loaned from the French word meaning “peasant’s smock” and appeared inexplicably in the early 19th century to describe the attire of French labourers. We know even less about the garment’s origin. Which raises the age-old philosophical thought experiment: If a blouse is worn before it is named, does it exist? What we do know is that it was neither noble, nor vogue. Certainly not pompous. If you wore a blouse at any time before the 1860s, you’d have been more likely to swing in on a beanstalk than a chandelier. Blouses were the garb on most farms and in many factories, and primarily worn by men and children. It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that it evolved from male peasantry.

The modern blouse owes much of its popularity to the Italian patriot Giuseppe Garibaldi. Many people don’t know that Garibaldi led two revolutions. The first was unifying Italy, which became a republic in 1861; the second was in women’s fashion. Garibaldi dressed his guerrilla army in red blouses, proving that even in mortal combat, Italians dress to impress. In a few short years, Garibaldi went from domestic folk hero to continental style icon. The battle blouse was known as the Garibaldi shirt and was donned most notably by the French empress Eugénie de Montijo. »For a considerable time Garibaldi was the most famous man in Europe, and the red shirt, la camicia rossa, became the fashion for ladies, even outside Italy, « writes the historian Egon Friedell.

Europe’s moneyed class quickly gentrified the emancipated red blouse, decorating it with Victorian pomp as if making up for lost time. No longer a shirt for fighters and farmers, the bourgeois button-ups of the upper class were made from finer materials and featured lavish details like lace embroidery and collars that crept up like vines. They also came in white. Simpler styles were adopted by the working classes, which were increasingly populated by women. The proletariat blouse was billowy but simple – picture a chef’s toque blanche. Meanwhile, men pledged allegiance to the clean-cut dress shirt as jobs moved from concrete to carpeted floors.

Through the turn of the 20th century and into the Roaring Twenties, blouses remained ostentatious for the rich and modest for the rest. Then the Great Depression put an end to pleats and ruffles. Blouse design turned austere and, with the advent of the Second World War, more utilitarian. Sleeves tightened and necks were liberated from high collars. Picture Rosie the Riveter’s denim blouse. The ’50s were marked by the »housewife« style – neat, yet dressy enough should a dinner party break out – until things started to get wild again in the ’60s. Blouses were so ubiquitous by then that it’s impossible to claim a defining style. Everyone was wearing them, from the monochrome tide of working women to the psychedelic flower power generation. Some looked like a Jetsons sketch, others like structureless jazz. The counterculture also inspired men to get back into blouses. Usually, they were artists. Jerry Seinfeld’s pirate shirt, owing to this era, is more commonly known as a poet’s blouse.

Which brings us to today. It is impossible to define the contemporary blouse. The modern stylescape is an amalgamation of every era that came before it. We have blouses with prints, pleats and in plaid, from lace to silk and chiffon to chambray. Buttoned, without buttons, unbuttoned, buttoned up, buttoned down. Peasant-style or with cold shoulders. And, with the dissolution of gendered fashion, blouses are once again for everyone.