Blasphemy! Religion vs. Renaissance art

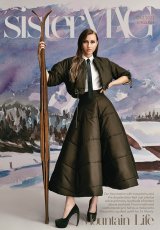

In simplest terms, to commit blasphemy is to act in a way that shows contempt for God or religion. Examples of blasphemy include burning the Bible or the Qu’ran, vandalizing a church, or worshipping satan. But it can also include less egregious offences, such as the flippant portrayal of religion and promotion of vanity, temptation, and sin through art. While blasphemy laws have loosened or been completely eradicated in many parts of the world since the 16th Century, both legal and extrajudicial punishments on the grounds of blasphemy still exist today. Christian Näthler introduces you in sisterMAG No. 50.

- Text: Christian Näthler

Blasphemy!

Religion vs. Renaissance art

In simplest terms, to commit blasphemy is to act in a way that shows contempt for God or religion. Examples of blasphemy include burning the Bible or the Qu’ran, vandalizing a church, or worshipping satan. But it can also include less egregious offences, such as the flippant portrayal of religion and promotion of vanity, temptation, and sin through art. While blasphemy laws have loosened or been completely eradicated in many parts of the world since the 16th Century, both legal and extrajudicial punishments on the grounds of blasphemy still exist today.

The etymological roots of the term »blasphemy« extend from the Middle English blasfemen, Old French blasfemer, and Late Latin blasphemare – to blame, slander, and speak evil of. To commit blasphemy means speaking evil of or attacking a very specific subject: God and religion. And it doesn’t have to be as blatant as setting fire to a church or tattooing the devil on your chest. Depicting heresy – beliefs or opinions contrary to orthodox religious, namely Christianity – through art is also considered blasphemous by religious authorities.

While most modern Christian societies enjoy a secular order, a separation of church and state in which art is protected under laws governing freedom of artistic expression, this was of course not always the case. In his 2006 book »Blasphemy: Art that Offends«, author S. Brent Plate writes, »no work of art is blasphemous in and of itself; it must be deemed so from within religious and/or political power structures … blasphemy needs both an artist and an accuser«[1]. When the Italian Dominican friar and preacher Girolamo Savonarola wrestled control of Florence from the ruling Medici, he seeked to strengthen Christianity’s grip on society. Part of establishing a pious republic was banishing from society the sins of desire – lust, gluttony, greed – born from the Italian Renaissance. That included Renaissance art. It’s not that religion had no place in art, because it certainly did. Savonarola’s problem was that the lines between divinity and pleasure became increasingly blurred.

This led to perhaps the fabled bonfire of the vanities, which took place in Florence on February 7th, 1497. Ordered by Savonarola and true to name, the bonfire saw thousands of objects burned under the new ruler’s divine mandate. The objects included art, books, cosmetics, ostentatious clothing, playing cards, mirrors, musical instruments, manuscripts of secular songs, and sculptures. Among the most notable works rumoured to have been burned in the fire are paintings by the Early Renaissance artist Sandro Botticelli. Irrelevant to the veracity of this account is the fact that Botticelli’s prolific career as an artist effectively came to an end after Savonarola assumed control of Florence. Botticelli was a loyal follower of Savonarola and willingly burned his paintings in partisan allegiance. Ironically, Savonarola was executed for heresy in 1498. Botticelli died in 1510; two years later, the Medici would briefly return to rule. Artists and scholars who feared they would be persecuted as heretics by the stringent Catholic church could again dabble in the pagan (unpure) origins of their faith[2].

Botticelli’s works reflect aspects related to paganism, a set of pre-Roman spiritual and religious beliefs considered uncouth compared to angelic Christianity. While we don’t know which specific paintings were burned at the bonfire, we can assume they alluded to pagan motifs. Of course, many of his masterpieces that endured also reflect impurities Savonarola will have deemed blasphemous. Botticelli’s most renowned work, »The Birth of Venus«, depicts the goddess of love as a noted adulteress whose affair with Mars gave birth to the god of sexual lust, Cupid. Another of his gems, »Calumny of Apelles«, is an allegory for hostility that defies the dignity of God[3].

Such representations would turn few heads today, even among the religiously devout. But in an age where the Catholic church seeked to increasingly exert control over every aspect of society, sin portrayed merely in allegory justified banishment on the basis of blasphemy.

[1] https://www.academia.edu/168359/Blasphemy_Art_that_Offends

[2] http://artcriticismtoday.net/the-game-changing-message-hidden-in-botticellis-primavera/

[3] https://www.patheos.com/blogs/henrykarlson/2019/04/the-blasphemy-of-calumny/