The »Tulip Mania« during the Golden Ages in the Netherlands

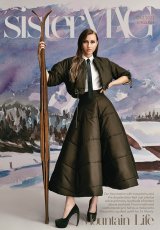

What do Bitcoin, the Dot-Com-favourites of the 1990s and Dutch tulips have in common? That’s right: insane speculations that led to financial ruin. Whenever large groups of people are drawn to a market they don’t understand – from crypto-currencies to software and bulbous plants – more often than not, the result is a crash. The first time this phenomenon appeared was during the Golden Ages of the Netherlands, when a whole nation went crazy for flowers. Christian Nathler summed up the most important points about »tulip mania« for issue 47 of sisterMAG.

- Text: Christian Nathler

»Tulip Mania«

Would you trade your house for a tulip?

How »Tulip Mania« during the Dutch Golden Age signalled the first major financial bubble

What do Bitcoin, the dot-com darlings of the 90s, and Dutch tulips have in common? If you guessed rabid price speculation leading to financial ruin, you’re right. When crowds rush into a market they don’t understand – whether it be cryptocurrency, software, or bulbous plants – the result is often the same: a crash. The first event triggering this phenomenon arose during the Dutch Golden Age when a nation went in a frenzy for flowers.

By all modern accounts, selling your house to buy a tulip would be a categorically terrible decision. But there was a time in history when that wasn’t necessarily true. To understand how or why such irrationality came to be, we have to rewind almost four centuries, to the Dutch Golden Age.

The 17th century ushered in an era of economic prosperity for the Netherlands, then known as the Dutch Republic. The young confederacy innovated trade with the Far East, bringing vast quantities of spices, silk, tea, grain, rice, soybean, and sugarcane to Europe. This was largely achieved through the government-propagated Dutch East India Company, which was like the Amazon of the Early Modern period. The world’s first multinational corporation, the company offered citizens an opportunity to contribute to and share in its wealth by offering shares of stock. Thus, the first official stock exchange was born. The capital generated by these economic activities saw the Bank of Amsterdam emerge as the first modern central bank, with the authority to control – and increase – the state’s money supply. Times were good for the Dutch. Furthermore, the republic imported essential goods from resource-rich European countries so that when crop harvests decimated in neighbouring countries, like they did in France and England, they would be forced to buy marked up essentials from the Dutch. Times got better for the Dutch, even as they got worse for others.

As is wont for the nouveau-riche, the Dutch developed a penchant for the ostentatious. Social status was not just a product of inheritance, but of purchase. The upwardly mobile civilization ate well, read well, and put nice things on their walls. It’s no coincidence that some of the most masterful art in the world originated from the Low Countries. And in such abundance. This was an opulent populace, and the De Jongs next door better recognize, damn it. Oh, and they also bought tulips.

As author Anne Goldgar writes in her book »Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age«, »As luxury objects, tulips fit well into a culture of both abundant capital and new cosmopolitanism«. They were also new and shiny, imported from the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century and publicized for the first time – in a book by botanist Carolus Clusius – just a decade before the founding of the Dutch East India Company. And it was up to a freer-than-ever market, now complete with investor speculation and complex financial agreements, to determine how much they were worth.

As tulip bulbs grew in prestige, their value skyrocketed. By the mid-1630s, a generation into the Golden Age, tulips were the nation’s hottest commodity, with only gin, herring and cheese as more valuable exports. Supply of tulip bulbs couldn’t keep up with demand. The price of a single bulb rose steeply, from the equivalent of a root vegetable at the beginning of the century to being worth as much as an entire estate towards the end of 1637. Skilled tradesmen would have to work more than ten years to earn enough money to buy a single bulb. It was tulip mania in the Dutch Republic.

But was demand really that fanatical? Quite the opposite. This new free market introduced what is today known as a »futures contract«, where one party agrees to buy something for a fixed price at a fixed time without having to know each other or any goods exchanging hands. In the fall, buyers would secure the right to buy bulbs for a predetermined price the next spring. These contracts changed hands up to ten times a day with each exchange driving up the price of bulbs a little higher.

By 1636, demand had dipped. That meant buyers locked into futures contracts from the fall were forced to pay more for bulbs in the spring than they were actually worth. Here’s where things get political. Many of the buyers were local mayors who were left scrambling to recoup their losses. Or they would have been, if it weren’t for some slick legal maneuvering. The indebted burgomasters enacted legislation that would turn their futures contracts into option contracts. That gave them the opportunity to buy bulbs if their price was higher than the price they had originally locked in. If it was lower, they could simply buy out the contract for a small compensation to the seller. This left sellers in a hole since they stocked up on bulbs with the assumption that their inventory would fetch a guaranteed price, as was agreed upon through the futures contracts. Instead, softening the contracts created a win-win for buyers while sellers were forced to cut their losses.

Sellers – planters and market vendors – therefore inflated the price of bulbs up to 20 times their actual value. The hope was that buyers would honour their contract, which was now an option and not an obligation. But the buyers didn’t buy it. They knew the inflated price didn’t reflect the market value, leaving vendors in possession of a toxic investment. Famously, a bulb auction in Haarlem – an epicentre of the mania – drew not a single soul. The price plummeted almost immediately, offering the first glimpse of what happens when people sell things they don’t actually own to people who cannot afford them.

Nearly half a millennium later, it appears as though we haven’t learned our lesson.