Women and the city of the 19th century

In the 19th century, women were not allowed to freely walk around the streets of cities. How did women eventually succeed in coming out to the European cityscapes legally? A little overview.

- Text: Barbara Eichhammer

Separate Spheres

„I wanted to be a man insofar as I could enter realms and milieus that were closed to me as a woman“ (George Sand)

At the beginning of the 19th century, city spaces, public life, and the workplace were regarded as predominantly male domains. According to such a bourgeois ideology of separate spheres, women of the middle classes were restricted to the home. The contemporary ideal of femininity was Patmore Coventry’s »angel in the house«, a domestic angel who devotedly cared for the family and home. Making it even more complicated was the fact that women who dared to move around the urban streets were regarded as either morally endangered or dangerous. If they wished to spend some time in the city, they had to be accompanied by gentlemen, chaperones, or servants. For women who were seen wandering the urban streets were mostly considered to be prostitutes or »fallen angels«, i.e. the Other of the bourgeois gender norm. In Paris and London, prostitution turned into a mass phenomenon at the end of the 19th century. In 1887, 80,000 prostitutes are said to have been working in London’s West End. But prostitution had nothing to do with free movement in the city: the women had to register with the police and health offices, as well as sticking to strict clothing regulations. Even the places where they could go were controlled.

The rise of the department stores

The rise of urban consumer culture and department stores such as Le Bon Marché (1838) on the Rue de Sèvres in Paris contributed largely to the fact that women could more freely frequent the urban streets. As the world’s first department store, Le Bon Marché offered its female customers public spaces within the city where they could spend time without male company and outside their domestic spheres. With their rise, department stores helped to normalise the image of women on urban streets during the 1850s and 1860s. Stores like Galeries Lafayette in Paris (1895), KaDeWe in Berlin (1907), and Harrods (1884) in London’s West End became popular daytime destinations. Tour guides recommended places in London where »ladies could eat lunch when they are without the company of a gentleman« as early as 1870. Thus, shopping itself turned into a public leisure activity for bourgeois women. When they walked the urban streets, they filled the city topography with cultural meaning and conquered the commercial marketplace. Walking can be seen in this context as an act of cartography with one’s feet. As French sociologist Henri Lefebvre explains, the city is a space which is actively constructed and created by our social activities. In this vein, women shopping created the cityscape by walking.

Shopping Angels & the modern city

This was made possible by the emergence of semi-public spaces within the cities such as cafés, ladies’ tea rooms, and the most intimate space of all: womens’ public toilets. The opening of the London Tube (1863) and Paris Métro (1900) further supported this development. Though women in Paris had to wait until the turn of the century for ladies’ restrooms to open, Aristide Boucicaut offered a crèche in his Bon Marché to make shopping as pleasant as possible. A new target group had been found: The female middle class. Critics, however, regarded the comfy interiors of the department stores as a continuation of the private sphere, a »home away from home«, so to speak, where the »shopping angels« still adhered to the bourgeois ideology of domesticity and were considered morally endangered. To buy something and to sell one’s body was one and the same in the imagination of 19th century men. Shopping was often associated with a sexualised femininity, which was underlined by the immediate geographical proximity of department stores to brothels. In London, for instance, the shopping district was almost next to the red-light district in Regent Street and Burlington Arcade. Thus, the modern city was imagined with the help of opposing discourses: On the one hand as a pulsating landscape of modern consumer culture, and on the other as a Victorian Babylon that put innocent women in sexual danger.

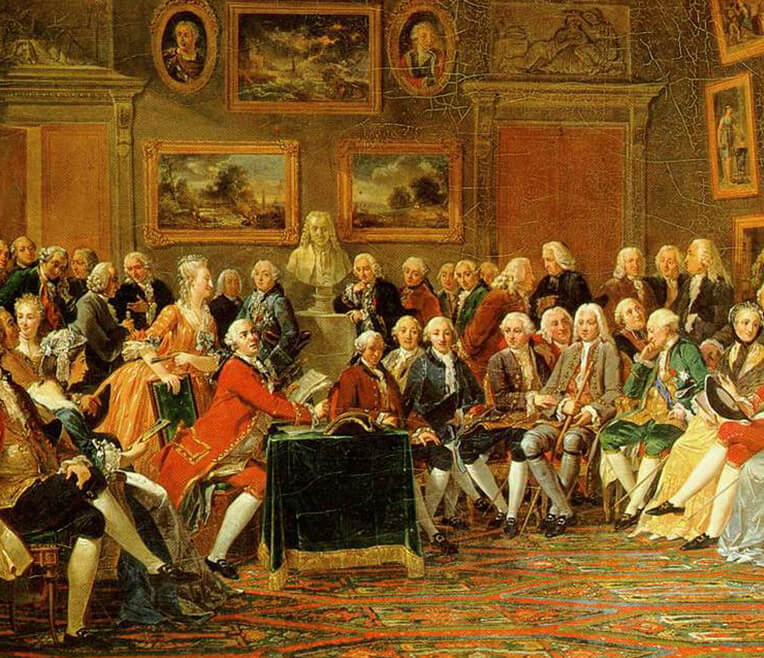

The salon as female cultural space

The literary salon was for aristocratic women what department stores were for women of the middle class. In general, the literary salon was a place of female culture, where guests got together under the direction of a woman, the salonnière, for educated conversation. Catherine Marquise de Rambouillet was regarded as the founder of the salon tradition. When she invited her guests to the Parisian city palais in 1610, she opened the first literary salon and founded a public space as an alternative to royal court: There was witty conversation, music, poem recitals, and small performances. Although the salonnières were themselves aristocratic, they lead their salons according to the principles of equality and liberty. During the 18th century, philosophers, literates, and artists like Voltaire and Didot loved to socialize in the salons of Paris and laid the intellectual basis for the French Revolution. Thus, the salon also established new gender spaces, which empowered women from a political and intellectual perspective – notably at a time when women were not seen as equal.

Rebellious Salonnières

During the 19th century, socio-critical writer George Sand used her literary salon as an adequate forum where she could voice her socio-political and feminist thinking. Rebel through and through, she broke with many gender stereotypes of the time: She was regarded as unconventional, illicitly smoked cigars in public, wrote under a male pseudonym, and loved to stroll around the streets of Paris in men’s clothing. As ancestor of the Comte de Saxe, she was herself aristocratic but moved in the circles of Paris’ bohemian society. Her salons in the French capital, as well as at her country estate in Nohant-Vic, were popular gathering places for well-known novelists such as Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert, and Alexandre Dumas, as well as composers like Franz Liszt or Frédéric Chopin, with whom she had a love affair. Salonnières such as George Sand, Marie d’Agoult, and Mathilde Bonaparte were so very popular during the 19th century that they gave women unprecedented cultural significance. Parisian salons were prevalent until the 1960s, like the literary salon of the US-American author Natalie Clifford Barney. She was well known at the time for her lesbian love relations and used to assemble famous European writers like Djuna Barnes, Gertrude Stein, Colette, Rainer Maria Rilke, Ezra Pound, and Isadora Duncan. Until today, the literary salons of the 19th century exert great fascination. Despite all class and gender boundaries, men and women came together to have educated conversations. To be visible as woman and walk the urban streets is still a highly relevant aspect in the 21st century, as the women’s marches in Washington, New York or London in 2017 have shown.