Holger, the dairy farmer

Photographer Andrea Lang visited Holger, the dairy farmer, on his farm and reports on her experiences and the traditional profession which is on the verge of extinction in sisterMAG No. 62. In a 2020 exhibition, the photographer captured many other traditionl trades in addition to the work of Holger on his farm.

Here you can read the previous text about the J.J. Hat Center and the hatter from New York.

- Text & Photos: Andrea Lang

Holger, the dairy farmer

The last of his kind

I remember it like it was yesterday, holding the milk churn in hand and strolling past the few houses to the adjoining farm to get fresh milk. The best part was the walk back: because the name of the game here was to skip home with the jug as fast as possible, but not let the lid fall off or the milk spill.

Not much has changed on the dairy farm since then. We still have the last dairy farmer in the Hamburg region in our neighbourhood, who milks and works in a very traditional way – his name is Holger Eggers. Holger’s parents already had the farm. I always remember Marianne with a headscarf, a smock, red cheeks and a smile. And Gustav with his faded overalls and a flat cap. Farmers – exactly how you’d expect them to look. Holger, their son, took over the farm in 1989 after completing a degree as a farmer. He still took a few courses in the winter semesters, such as claw trimming, general knowledge, and plant protection, and thereafter became a state-certified farmer. When I asked Holger when he started, he said: “You just grow into it. When I was 10 years old, I already helped out here and there.”

He wasn’t expected to take over the farm. But Holger enjoyed the animals, nature, and the changing seasons – with everything that goes with it He got an apprenticeship position on Hahnöfersand at a farm with pigs, cattle, bull rearing, and dairy cows with calves. He realised after that time that his focus would be on dairy cows.

Even though time seems to stand still on this farm, a lot has changed for the dairy farmers since then. The greatest change caused by the climate. “We don’t have proper winters anymore. The summers are either too hot or too wet.” Because the winters are so mild, Holger has noticed over the past ten years an increase in parasites and ticks on the animals. Another development, unfortunately not a positive one, is the increasing bureaucracy. So much has to be documented that soon 70% of the time will be spent on fertiliser regulations, plant protection, and the use of medicines. Holger says: “Wasted time of your life. And all that only for the case that an inspection takes place. Otherwise the documents just gather dust in a folder. Everything important is in my head anyway. I’d much rather be doing something productive, sustainable, something meaningful.”

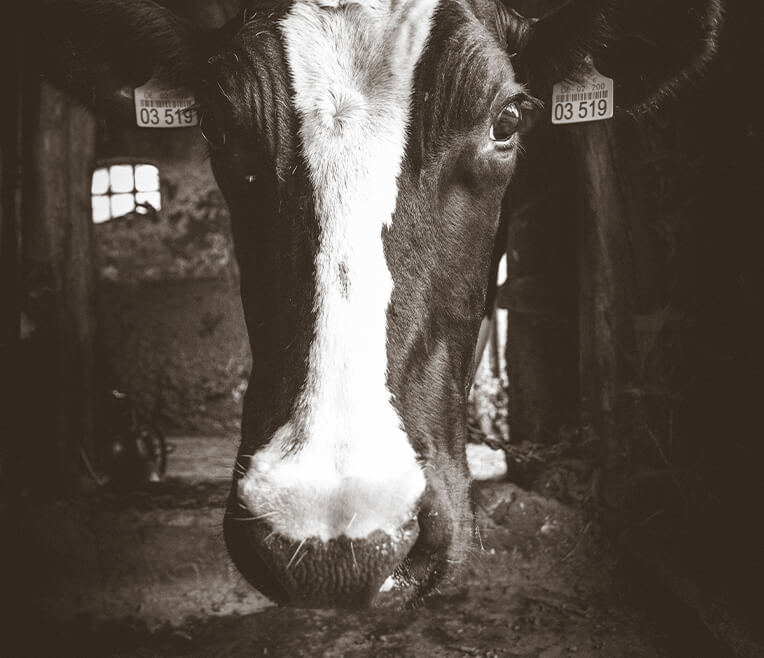

And there’s no shortage of meaningful work to be done. Holger’s cows are outside grazing day and night for at least 6 months of the year. He brings them in from the pasture at half past five in the morning to be milked in the barn. He is the last of his kind; someone who works in a traditional tethered way, directly into the milking buckets and amongst the cows. The milk is let directly into the milking buckets, which is then transferred to a large tank as the crow flies. The tanks are then picked up from the dairy farm every two days at a minimum of 6 degrees. Milking takes place in the mornings and evenings. In between, Holger’s everyday life consists of growing grain, using natural fertilisers, fencing areas to change pastures, mowing and making hay. The tall grass must be mowed at the right time and turned 2-3 times before it can be pressed into round bales and moved. This is all very weather-dependent. If it rains during the process, the hay has to be turned again to let the sun dry it out and prevent rot.

I asked Holger how it’s possible for one person to do all this work alone. Because I know that there are neither weekends nor vacations for him. And what if he got sick? Holger doesn’t know the word ‘flu’. Even if everything’s falling apart, the cows still have to be milked twice a day. Holger says: “When one door closes, another one opens.” He broke his hand once. But some time before that, a friend who was very stressed privately and professionally came to the farm, looking for a change of pace. So, they had worked together with the animals and the friend could step in when Holger was absent for a brief period. It’s not a rare thing for people to come to the farm and want to have a look around or help. The children in any case; just like I used to. But adults also want to be shown what the milking process looks like, or are in search of something missing in their lives. Because working with animals is therapeutic. A woman came to the farm recently and asked whether she could cuddle the cows. Holger allowed her to go to the pasture and try it. “They’ll let you know if they like it or when they’ve had enough.” His cows are used to human interaction, because Holger always walks around between them and is close to them when milking in the barn. There’s also petting while they do this, and that need for closeness. This isn’t possible with cows from large dairy farms where they keep 300 animals. A vet was recently totally amazed at how peaceful his animals are and that Holger talks to them by name. He was only familiar with the kind of milking farms where the cows bucked and kicked; it wasn’t possible to walk among them.

For the children who want to try his milk, Holger first asks them whether they dare to drink fresh unpasteurised milk. Because most of them only know 1.5% milk, which Holger affectionately calls “coloured water”. Holger has joined a dairy farm group that forms a cooperative with around 200 dairy farmers. His milk is later processed in the entire “white range”: the term refers to baby food, milk, yoghurt, and cream collectively.

Working with other farmers is crucial; in this way, you share the combine harvesting and running the pasture fields. Since agricultural machines are extremely costly, colleagues complement and support each other. Holger laughs heartily when he tells me how things often go when colleagues work together. Already in the morning, Holger says in the finest Low German: “Man to, man to, ward glieckst wedder düster.” (“Get a move on, get to work, it’ll be dark again soon.”) And his colleagues respond with: “Eggers, relax.”

When Holger started, the goal was to produce for the global market. This euphoria hasn’t been felt for a long time now. In his time as a farmer, he’s already supplied 5 dairy farms because 2 went bankrupt and others restructured. Only large companies are funded properly. While the production, wages, and energy prices are rising steadily, the milk prices are sadly similar to how they were in the 1970s/80s. Unfortunately, the actions by interested associations haven’t helped. For that reason, it remains up in the air whether there will still be small businesses in the future. Holger hasn’t found a successor yet. And that, despite the fact that the next generation would benefit greatly from many of the measures he’s implemented over the past few years. He pursued long-term goals and, for example, reduced the pH level of his soil from 6.2% to 4–4.5%. His meadows have been acclaimed as a nature conservation area.

It’s not financially feasible to keep 16–18 cows on 52 hectares of land. But to this day, he still loves working with animals and nature. “Germany will soon no longer be able to sustain itself,” says Holger. And so my childhood memories will soon fade. Children will no longer be able to saunter into the stable and let the newborn calves suckle on their fingers or swing the milk churn while skipping home.

—

In her long-term photographic project “Altes Handwerk & Traditionsberufe” (“Old Crafts & Traditions”), the Hamburg photographer Andrea Lang shows craftsmen, old and traditional professions, jobs with passion and professionalism. Simple, enacted, old-school black and white portraits, inspired by August Sander. In contrast to her advertising shoots with a photo concept, these photos aren’t staged for long, but rather have a reportage style without any major staging. “I was blessed to hear incredibly exciting stories, meet people who were enthusiastic about their work, and gain great insights into workshops and working methods. One of them asked me what my motivation for this series was. It’s always been important to me for my photos to tell a story. I see how much is being forgotten and I want to keep some of it alive.” During her research, the photographer found out that the profession of carriage building no longer exists in Germany. “It just doesn’t make sense anymore,” she was told. In September 2020, Andrea Lang managed to hold the first photo exhibition on the project in an open greenhouse. 23 portraits, presented in vintage iron window frames, swayed in the wind and connected with the idyllic surroundings and nature. The first step to remembering that high-quality craftsmanship also needs to be remunerated, was taken. And thus, perhaps also the first step to not letting an almost forgotten craft die out.

Here you can read the text about the hatter from New York in sisterMAG No. 61.